|

[ BACK TO AL HAZAN HOME PAGE ] [ BACK TO AL HAZAN HOME PAGE ]

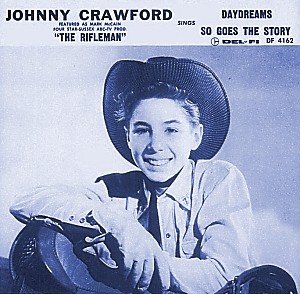

Johnny Crawford and "Daydreams" HEAR Johnny Crawford and "Daydreams" HEAR

In May, 1961, Johnny Crawford made his recording debut with "Daydreams" a song written by Al Hazan, recorded at Gold Star studio in Hollywood, and produced by Bob Keane.

Johnny was the 14 year-old juvenile star of the popular TV show "The Rifleman", but had never sung professionally. However, Bob Keane, the owner of Del-Fi Records, felt Johnny had the looks and personality to arouse the teenage girls who were the dominant market in popular music.

After 3 months of singing lessons paid for by Del-Fi, Johnny turned out to have a pleasant, light tenor voice. "Daydreams" reached No. 70 on the Hot 100, giving Johnny a promising start to his new singing career.

Other movie and television stars of the 1960s who recorded Al's songs include James Darren ("Fool's Paradise"), Yvonne De Carlo ("The Secret of Love") IMAGE, Jimmy Boyd on the T.V. show "Batchelor Father" ("It Makes Me Wanna Cry") IMAGE and the three "Bradley Girls" of the T.V. show "Petticoat Junction" ("Three of Us").

But that wasn't the final version of "Daydreams" to hit the record racks. Al later worked with the well-regarded Charlotte O'Hara to record another version under very different circumstances. He tells the story:

A few years after the Johnny Crawford release of Daydreams, I met a young singer named Charlotte Matheny. We became good friends and I often had her try out songs and sing demonstration records with me.

Charlotte and I were both friends with Stan Ross, the co-owner of Gold Star Recording Studios. In June 1964, while I was recording at the studio, Stan asked if I would do him a favor. He asked if I would produce a record for him some night so he could show the members of his social club how Top 40 recordings were made. He said I could produce anything I wanted to, and added he would give me the studio time, the equipment and furnish the recording tape and his engineering talents.

I told him I'd be happy to. I also suggested Charlotte do the vocal since I was working with her on a song of mine she wanted to record. He liked the idea and said he would ask the musicians we usually worked with to play on the session and felt they'd be happy to help for free. It all turned out to be true. I guess we all subscribed to the concept that what was good for one was good for all, so the cost of producing the record was zero. I told him I'd be happy to. I also suggested Charlotte do the vocal since I was working with her on a song of mine she wanted to record. He liked the idea and said he would ask the musicians we usually worked with to play on the session and felt they'd be happy to help for free. It all turned out to be true. I guess we all subscribed to the concept that what was good for one was good for all, so the cost of producing the record was zero.

We got together in Studio A at Gold Star on Saturday night that same week. I decided to play piano on the session so I could communicate easily with the other musicians. The band included Ray Pullman on Fender bass, Tommy Tedesco on guitar, and Hal Blaine, our favorite drummer.

Stan had invited about twenty members of his club to the session, and they crowded into the recording booth, which measured about 8 by 12 feet. Some stood in back of Stan and the control board and some sat down in front. It felt strange for us in the studio to see so many people through the glass as we rehearsed the rhythm track.

This was a wonderful opportunity for everyone, especially Charlotte and myself. We had no "angel" or financial backer to please, or record executives looking over our shoulder; it was just Charlotte, Stan and me and some of our favorite musicians making a record for our own enjoyment. It was a treat offered rarely to an independent producer such as I was then. The song we recorded was "Daydreams."

Our "audience" seemed fascinated as we went through the standard process of playing each instrument individually, having Stan blend them together for balance. These musicians were great to work with, and it was relaxed as I taught them the parts I wanted them to play. The session went so smoothly, it took less than an hour to complete the basic rhythm track and let the musicians make their exit. Since they had done the recording as a favor, I'm sure they were happy to get home early on a Saturday night. Stan and I thanked them for their time and effort and said we'd all be working together again soon.

It was Charlotte's time to sing lead vocal while I handled background voices myself; getting the vocal track down took about 40 minutes. Charlotte never seemed satisfied with her performance and she kept asking for just one more take to get it right. Actually, her vocals were all wonderful and I finally had to tell her it was enough after around 15 takes. I reminded her we could always splice over any part of her vocal she didn't like. It was Charlotte's time to sing lead vocal while I handled background voices myself; getting the vocal track down took about 40 minutes. Charlotte never seemed satisfied with her performance and she kept asking for just one more take to get it right. Actually, her vocals were all wonderful and I finally had to tell her it was enough after around 15 takes. I reminded her we could always splice over any part of her vocal she didn't like.

This option of splicing the tape was often exercised when recording a session. Although the producer may have a preferred vocal take of a song, there might be a word or phrase that didn't come out well. In that case, the engineer could simply splice the unwanted part out and replace it with a copy of the same phrase taken from another vocal take. Engineers in the 1960s were masters with a razor blade and spicing tape.

After reminding Charlotte of this option, she agreed to stop worrying about her performance and sat down. As it turned out, the recording was released as she performed it, without any splicing or editing and she was happy with the final product.

Charlotte remained during the mixing, along with the club members who still looked on. Stan and I took another half hour to blend the three tracks - the rhythm, the lead vocal and the background voices - into a final monaural master. The whole process, start to finish, was done in about two hours, starting around seven o'clock and finishing a little after nine. I was thrilled with the results and could tell Stan was also as he presented me with the master tape and a vinyl copy of "Daydreams" to do with as I wished. What a fun and creative night for us all.

The day after, I took a tape of "Daydreams" to the fairly new company, Ava Records, owned by famous dancer/singer/movie star Fred Astaire. Ava Records was named after Mr. Astaire's daughter and was located near the corner of Selma and Argyle, in the heart of Hollywood. Jackie Mills, executive head of the company, liked the recording of "Daydreams" so much he asked not only if he could release it, but if I would join the company as their Top 40 A&R man.

That free 2-hour session got me a great job offer with a record label willing to pay me $500 a week for my exclusive services as their producer. Ava Records had been recording mostly jazz groups like the Pete Jolly Trio and fine artists such as Elmer Bernstein and Carol Lawrence. Jazz groups didn't cost much to record but recording big artists like Ms. Lawrence was expensive, so the company was spending a lot of money and not making enough in return.

I guess Jackie Mills felt young blood might turn things around for them financially and they hoped I might be the person to do it. I saw it as a terrific opportunity to be with a young company with an excellent reputation. The whole idea was exciting for me; I would have the financial backing I needed to record new artists, and besides, working for Fred Astaire obviously held a certain glamorous appeal.

Unfortunately, by the time I finished producing the sessions that completed Ava's outstanding contractual obligations, it was too late to produce the Top 40 artists I was rehearsing. Fred Astair was unwilling to invest any more money into this losing venture and Ava Records closed its doors.

[MORE ABOUT JIMMY BOYD]

[MORE ABOUT JOHNNY CRAWFORD]

[MORE ABOUT JAMES DARREN]

[MORE ABOUT YVONNE DE CARLO]

[MORE ABOUT BOB KEANE]

[MORE ABOUT CHARLOTTE O'HARA]

[MORE ABOUT PETTICOAT JUNCTION]

[MORE ABOUT THE RIFLEMAN]

|